Struggling in Silence: Disordered Eating Was My Dirty Little Secret

|

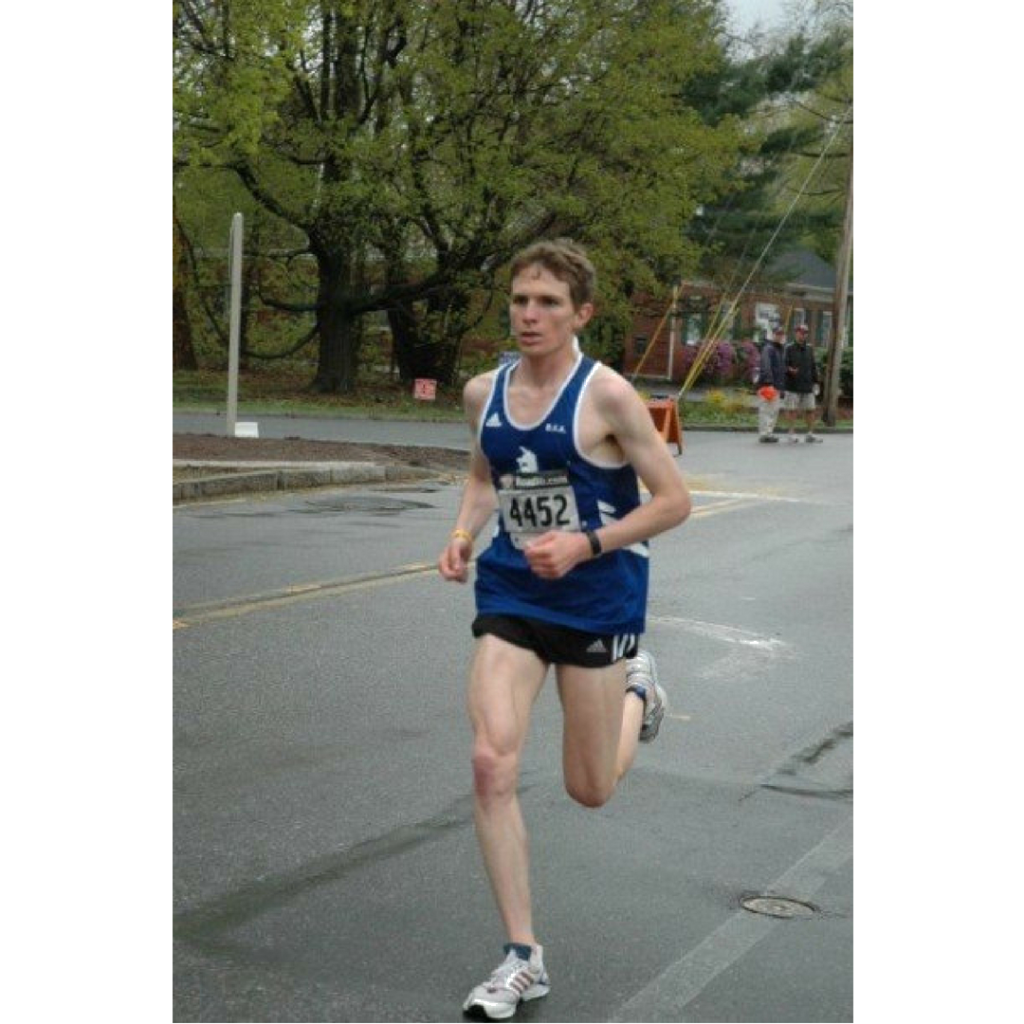

This was me 13 years and about 20 pounds ago. I was one year out of college, where I was an NCAA Division II All-American in cross country and qualified for indoor nationals in the mile. And you wouldn’t necessarily know it by looking at this photo, but I was silently struggling with disordered eating at the time. In an attempt to take my running to the next level, I convinced myself that I needed to better “look” the part of an elite distance runner. So I ran a lot—90-105 miles a week most weeks—but I also cut calories, swore off snacking, didn’t allow myself dessert, and made sure that I didn’t eat or drink after 8 PM. I obsessively tracked every calorie—less than 2,000 a day—and weighed myself at every opportunity.

I lost a lot of weight in a short period of time, but I was never skinny enough (which, I convinced myself, was why my race times weren’t getting faster). The numbers on the clock or in my training log hardly mattered much anymore. Ten miles wasn’t 10 miles, or even a good workout. No. Ten miles was roughly 1,000 calories burned, which is not how you want to be thinking if your real objective is to compete at a high level. I was in a bad place, not just physically, but mentally, emotionally, socially, and otherwise.

Fast forward a bit: I eventually turned the corner and adopted a much healthier relationship with food, my body, and running. But two years of unhealthy behavior caught up to me. Lower bone density contributed to three major stress fractures—two in my sacrum and one in my pubic symphysis (which, the orthopedist told me, he usually saw in elderly women and birthing mothers)—while the integrity of my fingernails and toenails suffered, I experienced regular bloating, and also saw increased instances of tooth decay, among a smattering of other issues I still deal with today.

My story isn’t a unique one. Eating disorders are an issue in running—in many sports, for that matter—and at all levels. As Riley Nickols says in this recent Washington Post piece I was mentioned in, “It cannot be ignored.” Male or female, elite or amateur, if you’re struggling with disordered eating and/or body image issues, you don’t have to feel isolated, alone, and ashamed. These aren’t easy things to talk about—particularly for men—but they’re important topics of discussion. It’s my hope that sharing my story can help others who see similarities in their own struggle, and inspire them to seek help or make a positive change. If that’s you, and you’re not sure where to turn or who to talk to, please don’t hesitate to reach out. I’ll do what I can to help point you in the right direction.

The Full Story: Weight Off My Shoulders

In December of 2004, I was messing around online when I stumbled upon “The Thin Men,” a lengthy piece Kevin Beck wrote a few years before for Running Times that went in-depth on the taboo topic of eating disorders among male distance runners. I was fresh out of college and, unbeknownst to me at the time, in some of the toughest stages of my own struggle with disordered eating and body dsymorphia. Beck’s piece really hit home. I was reluctant to admit to anyone—most importantly, myself—that I had a problem. Luckily, that article, along with a well-timed injury (sometimes they really are a blessing in disguise) and a lot of support from family and friends helped me to not only recognize the damage I was doing to myself, but also to take the steps toward turning around a bad situation.

Men don’t like to talk about eating disorders, but that doesn’t mean it’s an issue that shouldn’t be discussed. I know there are many other men (and women) in a similar situation to the one I found myself in as a Type-A 22-year-old, which is why I’m resurrecting (and updating) an old blog entry from 2006 and sharing my story below. Read it. Talk about it. Share it. You never know who it might help out.

This story starts in May of 2004, shortly after I graduated from tiny Stonehill College in my native Massachusetts. The running joke amongst my family and friends was that I majored in cross country and minored in track. I was an NCAA Division II All-American in cross country and a national qualifier in track with personal bests of 4:09.77 for the mile and 14:39 for 5000m, both school records at the time. Those accomplishments weren’t going to land me a shoe contract, but I didn’t care. I decided to pull out all the stops and commit the next four years toward qualifying for the 2008 U.S. Olympic Trials. Achieving that goal become the sole focus of my life, my raison d’etre.

In my first few months as a post-collegiate runner, I ran twice a day almost every day, tried to get at least eight hours of sleep every night, traversed soft trails at every opportunity, got regular massages and did pushups and situps after every run. You name it, I did it. If there was a box to check, I checked it—sometimes twice for good measure.

I also came to the conclusion that if I wanted to be an elite-level distance runner, I also needed to look the part. At 5 feet, 8 inches and 145 pounds, I hardly classified as being overweight, but dropping a little weight in order to more closely resemble the ectomorphic whippets I aspired to be like would surely keep me going in the right direction, right?

Wrong. The only direction I was heading spiraled downward, even if I didn’t know it.

So, in addition to training harder than I’d ever trained before, I worked on “improving” my diet. I cut calories, ate smaller (and fewer) meals, swore off snacking, refused dessert and made sure that I didn’t eat or drink after 8 p.m. For someone who was raised in an Italian household with an award-winning sweet tooth, this was a drastic behavioral shift. During this time, I also developed a mysterious lactose intolerance (self-diagnosed, of course), convinced myself I couldn’t digest meat anymore and drank more water than a Saudi Arabian camel. I counted every morsel that went in my body and capped my daily caloric intake at less than 2,000, usually far less, no matter how many miles I ran that day. All this just to drop a few pounds. Scary thing is, it worked.

That summer, after working part-time and running a slew of 100-mile weeks, I joined an upstart post-collegiate training group in Eugene, Ore., a small college town 3,000 miles away from home where I knew exactly no one. In the three months between graduating from college and moving out to Eugene, I successfully lost 15 pounds. Jenny Craig would’ve been proud. The only problem? I didn’t have 15 pounds to lose. And it didn’t stop there. In Eugene, where I had next to no money and very few friends, my downward spiral picked up steam. Instead of focusing on how fast I could go, or how many miles I could run, my main mission every day was to see how many calories I could burn. It became a game. I got more excited by seeing low numbers on the scale than I did by seeing faster splits on my watch.

Fast forward six weeks after my arrival in Eugene. Lonely, bored and broke, I packed my bags and returned home to Massachusetts weighing a famished 124 pounds. My family and friends barely recognized me. While people noticed changes in my eating habits and behaviors, the most common comment I received was usually along the lines of, “Wow! You look like you’ve been doing a lot of running.” Yes, I was doing a lot of running, but 10 miles wasn’t 10 miles, or even a good workout. No. Ten miles was roughly 1,000 calories burned, which is not how you want to be thinking if your real objective is to compete at a high level.

My downward spiral continued through the fall 2004 racing season. I joined a local club, kept up my 100-mile-per week regime, did regular speed workouts, jumped in a few races and performed poorly in most of them. I couldn’t figure out why I was racing so bad, but surmised it had to do with a training error of some sort. I also weighed myself three or more times a day, couldn’t fall asleep at night (and woke up starving when I did), continued to count every calorie, skipped some meals altogether and read every piece of nutritional literature—and food label—I could get my hands on. It all caught up with me at the end of November, however, when I started feeling some tightness in my left Achilles tendon. Naturally, I tried to run through it. A week later, I couldn’t run a step. In fact, my Achilles hurt so bad I couldn’t even wear shoes.

So, with all this newfound free time on my hands, I needed to find a way to fill the voids not running left in my day. I bought a gym membership. I cross-trained like a madman. I read massively. And I barely ate anything.

One day, while gathering all the information I could about caloric needs for the running wounded, I came across Beck’s aforementioned article for the first time and a light bulb went off in the black hole that housed my brain. Steve, the subject of The Thin Men, sounded a lot like me. His thinking and behaviors were eerily similar to my own. Could eating really be my problem? I quickly dismissed the question, but it stuck around long enough to get the wheels turning in my mind.

A few weeks later I was catching up with a friend on the phone. I told her about the nutrition guidebook I had recently bought with a Christmas gift certificate. She blasted me for my purchase and called a spade a spade. “Why did you buy that?” she asked, asserting her lingering suspicions that something wasn’t right with me. “Give me an honest answer.” I couldn’t, so I hung up the phone.

The next night I called her back and apologized for my rude behavior. I also vocalized all the thoughts that had been passing through my head since I hung up the phone on her the night before and admitted for the first time that I had a problem with an eating disorder. Thoughts of my body image, weight, food and calories consumed my life, I told her—not dreams of qualifying for the Olympic Trials. We talked for almost two hours (an eternity for me on the phone) and I immediately felt much better, but I also knew that I had a long road ahead of me.

I was able to start running again in February 2005 after my Achilles injury had fully healed. Aware of what my bad behaviors did to my body and mind—and how that affected my relationships with other people—I committed to taking better care of myself and talking more openly about my issues. I started eating more, and more often. I stopped counting calories. I quit reading nutrition books. I stopped weighing myself. I allowed myself to enjoy dessert again. Slowly, things began to turn around for me. Within a few months, I noticed I wasn’t tired all the time. My mood improved. I started sleeping better at night. I also started running fast again and a whole slew of nagging injuries that had been plaguing me for some time were finally starting to subside.

Those demons are pesky little buggers, however, and they’re always trying to find a way back into your life. In my case, they returned again in the fall of 2005, and at first I wasn’t very successful in fending them off and reverted to some of my past behaviors. But this time around, with the help of my parents, my old college coach and a few close friends, I was able to put the brakes on that downward spiral before I totally lost control.

Despite turning the corner and adopting a much healthier, more balanced way of living, I later paid the price for my nearly two years of unhealthy habits in the form of lower bone density, which led to multiple stress fractures in my pelvis and hips. The integrity of my fingernails and toenails suffered, I experienced regular bloating and also saw increased instances of tooth decay, among a smattering of other related issues.

Fortunately, I’ve been able to resume (and maintain) a healthy relationship with eating and my own body image. I enjoy food and don’t feel ashamed of how I look. I eat a healthy, balanced diet and don’t obsess about how much food I’m putting into my body. And while I never realized my goal of qualifying for the Olympic Trials, I still race and love to compete. Running has never been more enjoyable than it is today and I have a deeper appreciation for all the great people and opportunities this sport has brought into my life. I’m a very lucky guy.

There are other guys (and girls), however, who aren’t so lucky and find themselves stuck in the downward spiral I just described. Disordered eating isn’t an easy thing to talk about—especially for men—but it’s an important topic of discussion, especially among runners and other performance-minded athletes. It’s my hope that sharing my own tribulations—and triumphs—can bring more attention to an often overlooked issue and inspire others who may find themselves in a similar situation.

RELATED READING: Here’s a Q&A I did with earlier this year with Samantha Strong from Lane 9 Project.