Going Long: An Interview with Stephen Lane

|

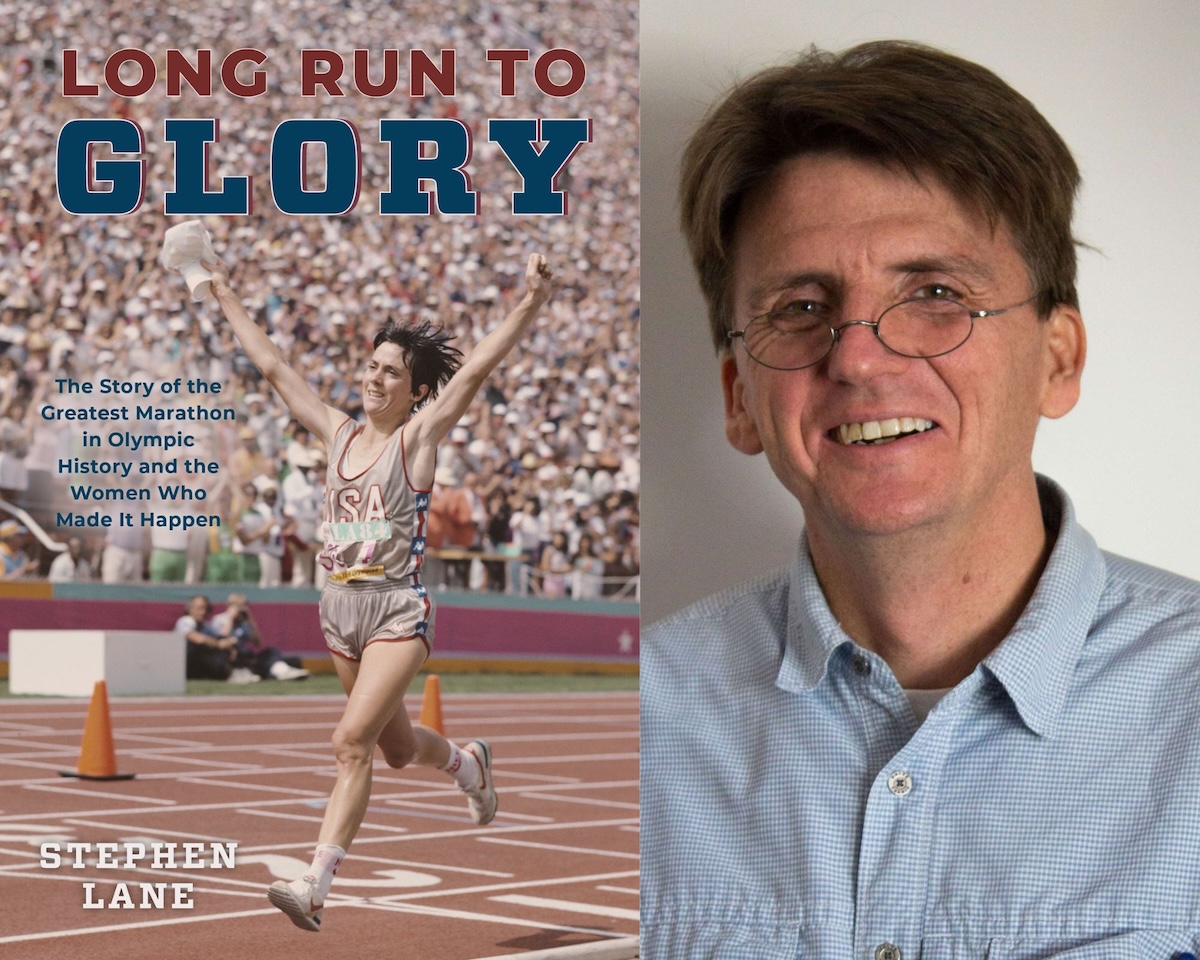

I recently conducted an interview over email with Stephen Lane, author of the new book, Long Run to Glory: The Story of the Greatest Marathon in Olympic History and the Women Who Made It Happen. This book tells the story of American Joan Benoit, Norwegians Grete Waitz and Ingrid Kristiansen, and Portugal’s Rosa Mota—four of the greatest marathoners of all time—and the story of how all of them lined up to race each other for the first time at the first women’s Olympic Marathon in 1984. Despite the fact that this race happened nearly 40 years ago, I think it should be required reading for anyone who considers themselves a fan of the sport, no matter their interests, age, or how they identify. It’s that important of an event in the history of women’s running and women’s sport in general. Add it to your holiday wishlist. I really enjoyed digging into the backstory of the book with Steve—himself a history teacher, track coach, meet director, and husband of my former teammate and training partner, Jess Minty—and I hope you’ll take the time to read our exchange below.

Why did you want to write this book and share this story? And why now?

Sometimes an image just gets stuck in your head. I was 13 when the race happened. My family wasn’t a running family, but we were huge sports fans, so if the Olympics were happening, we were watching on TV. I can remember coming downstairs that morning and seeing Joan Benoit on the screen, all alone on the Marina Freeway–a small gray figure in a massive expanse of concrete. Even though I knew nothing about marathoning, I could feel that something special was happening.

Broadly speaking, to write well, you have to write about things you love–I think that’s pretty obvious. But for me, the love manifests more like a pebble in my shoe, or more accurately, a piece of grit in my brain: I write the stuff I absolutely have to get out of my head, because I won’t feel good about myself until I do. Most of the stuff goes nowhere, might never be publishable, but I have to at least get the words down.

I can’t exactly tell you why that memory of the 1984 marathon became the story I had to tell now, but it did. And once it did–once I began researching it, outlining the possibilities, identifying the people I’d write about, it really took hold of me. The full story–both the race itself and the fight to get the marathon into the Olympics–is so compelling. And it is a story populated by remarkable people–the athletes who contested the actual race, and the pioneers who opened the doors for women to run marathons in the first place.

I’m fifty-something now. I’ve been involved with the sport as a runner, coach, meet director, and writer for a looooong time, and I’ve seen and experienced all the greatness and tragedy that running has to offer–and still, that image is iconic, and that race only gets better as it ages.

Given that this race happened nearly 40 years ago, how tough of a sell was this story proposal to publishers?

Let me preface by saying two things: First, if you talk to anyone in publishing, they’ll say it’s in a really tough place right now. (Though I also get the sense that people have been saying this since Gutenberg invented the printing press.) It’s a brutal business, and I have a lot of sympathy for editors and publishers. Second, if you’re going to write anything for publication, you have to be very comfortable with rejection. In fact, being told no is heartening, because at least they took the time to respond. Most often, you hear nothing; occasionally, you’ll hear, “this is great, but doesn’t fit with our direction,” or “our sales team doesn’t see a market.” Very, VERY rarely, you hear, “Let’s set up a meeting to talk further!”

That said, I got frustrated that publishers didn’t see the same sales potential I did (and do). My favorite comp was (and is) Boys in the Boat, an absolutely fantastic book about a long-ago race in a niche sport. If that book lands with people, so can a book about the 1984 Olympic marathon. And, I felt publishers’ responses reflected a certain ignorance about Benoit’s and Waitz’s status in the sport. For runners of a certain age, they’re like gods, and I think male runners are more likely to admire or even idolize female champions, because most of us have been in races where we’ve gotten clocked by the top women. Male tennis players don’t get the experience of trying to return serve against Serena Williams, but we runners have the privilege of finishing well behind the top women at major marathons. So I never thought of this book as a women’s book–I thought it had potential to reach a broad audience–but it was hard to get that across to publishers. But that’s the game.

For what it’s worth, we’ve already sold out the first printing and are into the second run, so that’s a good sign.

You’re a history teacher by trade. How did that influence your approach to researching this story and the various characters involved?

I’m a complete history nerd, and in early drafts, I researched and wrote way too much about things most people don’t care about! I wrote two full chapters on the influence of industrialization and urbanization on the rise of organized athletics in the 1800s and early 1900s–and cut them out because in that version, Grete Waitz and Joan Benoit didn’t even appear in the book until page 150-something. In short, my history nerd-dom meant I over-researched things that were only tangential to the story, and let myself go down way too many rabbit holes.

If the first key to good writing is to write what you love, the second is to understand that readers don’t want to read about everything that you love–you have to make sure the story stays focused on the story. Stephen King wrote an excellent book on his writing process, in which he says you should write with the door closed, then revise with the door open. In other words, write only for yourself, but when you revise, be mindful of your readers. So I tried to bring the focus back to the main narrative, and get rid of a lot of stuff that only I and a handful of other folks would be willing to wade through.

Still, even though it took a lot of time to research and write the chapters I cut, I wouldn’t say that was wasted time. I loved the process, and all that historical context was part of the grit in my brain I had to get out.

And in the midst of all this researching-writing-revising, I took heart from a line by Hemingway (apparently this is my day for name-dropping famous authors):

“If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.”

Yeah–Stephen King, Ernest Hemingway, Stephen Lane. Not in my wildest, most pretentiously hallucinatory fantasies would I compare myself to those two. But I do hope that even the stuff that I cut out helps make the story better.

Ha! I’m sure that it did, because as you noted, it serves to keep the main thing the main thing. On that note, who was the reader you had in mind when working on the book?

Many different readers, at different times!

I knew I would be dedicating the book to my wife Jess, who ran professionally for ZAP Endurance, and made the Olympic Trials for the marathon–so she was on my mind a lot. I also have a friend who helped a lot with the book, and we talked once about sports books that really give you a nice blend of historical context–I thought about him, even when I cut a lot of the history out! And I tried to keep non-runners in mind–I wanted a book that would be accessible to casual sports fans, that would give them some insight into this sport that I love so much.

Above all, I thought a lot about the people I interviewed–not so much the contenders from that race, like Joanie or Ingrid, but the pioneering generation of athletes and activists of the 1960s and 1970s. I wanted them to read the book and think, “Yup, he got it right.” (And I’ve been very pleased by the response so far: two early pioneers, women who rarely see eye-to-eye, both wrote me to say they loved the book; one said it made her cry twice–which might be the nicest thing anyone’s said to me about anything I’ve written.)

The structure of the book is really interesting, with a lot of stories weaved into and around this greater narrative of the 1984 Olympic Marathon. I’m interested to hear from you how that all came together, whether you had an idea of that’s how it would go, if if it kind of came together like that as you were working on it.

The final structure was the result of a fairly tortured process. I tried organizing the book a bunch of different ways: I started one draft with Joanie and Grete as kids, one with the industrial revolution, one started midway through the race itself… I even tried beginning with the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair (long story). One of my friends read the first couple chapters of an early version and told me, “this is really good, but this isn’t the book you say you’re writing.” So I knew what I was trying wasn’t working.

One problem with a book like this is that you’re building toward a single event, but that event is only a moment in time. You want readers to feel the importance of that event, to become emotionally invested in the outcome, and one way to do that is to spend a lot of time building up its historical significance. But then you risk short-changing the event itself–taking too long to get there and not having enough on the race itself, which would feel anticlimactic. But if you go too far the other way, by short-changing the backstory, the reader won’t get a feel for the event’s significance, and the book will feel shallow.

It was actually an editor who ended up passing on the book who suggested trying to bring the race forward, earlier into the book, by letting go of a linear chronology. I liked the idea, and saw it also as a way to add in some of that history I’d cut. So I used really brief interludes to give readers some of the backstory of women’s running in the Olympics before 1984. And then I continued adding interludes to get readers into the race earlier sooner, in a way that I hope builds suspense. It took a bit to sell my editorial team on the structure, but I think it works really well. I hope readers agree.

As a reader, I would agree with that! To what you said earlier, and I’m just being honest, I’m not sure I would have even made it to page 150 if the early version of the book had held up. But the way you ultimately structured it hooked me from the get-go. In a sense, I came for the race drama, but I stuck around for the backstories.

Thanks! Funny thing, I just gave a talk about the book at the school where I teach, in which I covered the history in detail–and then explained why I had to cut it from the final version. And my colleagues in the history department all told me afterwards that they found the history stuff the most interesting. But, they’re like me–complete nerds.

What, if anything, surprised you in the reporting on and writing of the book? Or maybe another way of phrasing that is, was there anything you learned that was wildly different than what you previously thought or knew?

So much! You don’t realize how little you know about the things you think you know until you start writing about them. It might be easier to list the things that weren’t different from what I thought I knew.

But here’s the biggest one–and it is something I should have known or understood from the beginning: just how human the athletes at the center of the story are. They all struggle with the same doubts, feel the same pressure, and get just as nervous before big races as the rest of us. Even post-race: many people experience a sense of loss or emptiness after a major marathon–it was no different for Benoit or Waitz.

And if you go back to their childhoods, they are just trying to be normal kids and fit in the way kids want to–but the fact that they aspired to be competitive runners set them apart from their peers, and in some cases, put them at odds with their families! Remember, they came of age with no real role models in the running world: Benoit was 15 when the Olympics finally added the 1500m for women. I spent a lot of time thinking about how teenage Joan or Grete navigated the difficult path to becoming the runners they became.

Further, even though Benoit and Waitz are absolute legends, they were also asking the same almost existential questions we all ask–whether about running, or our careers (which for them, was the same thing): Am I good enough? Am I working hard enough? Is all the effort going to be worth it? What, in the end, will leave me feeling fulfilled in my life?

Add to those sorts of concerns the fact that Benoit and Waitz especially are / were true introverts–yet both recognized their responsibility as public figures, and served in that role with grace and patience. I don’t think it was ever easy for them–I think it was utterly exhausting. But they did it, and did it well.

So in writing the book, I was struck over and over again by their humanity, and I tried to get that across in the story.

I appreciated that aspect of the book, and I know other readers will too. It reminded me of something the great Meb Keflezighi told me years ago: “The only difference is the numbers on the clock at the finish line.” Reading about these women’s challenges, doubts, and questions makes what could be interpreted as an unrecognizable pursuit relatable, at least on some level. As a writer, was it challenging to convey those things as a part of the story or did it help make it easier to tell in some ways?

It did not take very long for me to realize that I needed to focus on that part of the story. As I researched and wrote, it became the most important part to me. The challenge was this: Benoit and Waitz are both such stoics. And very private people. During their careers, they really didn’t want to give away anything.

I interviewed Jack Waitz a number of times, and he was able to give me a lot of insight into Grete’s mindset. But even now, Joan is not interested in engaging in any deep introspection with interviewers–which I totally respect.

But if you dig deep enough into their past interviews, every now and then, they’ll give something away. And Joan’s memoir is a little more open than you might expect–if you know how to look at it. I paid very close attention, and spent a lot of time analyzing what I heard and read. It’s much the same as what you do as a coach: We both know athletes might not always tell us everything, so you observe closely, pick up on cues, and draw conclusions.

Now, when I was writing, I took pains to qualify what I wrote if I didn’t have direct evidence or quotes from the sources. So I used “it seems as though,” or some such phrase if I’m drawing my own conclusions, because I can’t say for certain. But I do believe I present a pretty accurate analysis of their mentalities.

The book has been out for a couple months now. I’m curious about the response that you’ve gotten, both from some of the real-life characters that were part of the story, as well as others from the “outside” who’ve read it?

Obviously, if you write a book, you want people to like it. In this case, I felt something closer to a responsibility: this story is such an important one in running, and the characters who populate it are absolute legends (or should be). I desperately wanted to do the story justice. My primary reaction to readers’ responses so far? RELIEF! One of the women who plays a prominent role in the book called me to tell me she cried twice while reading it; another told me she read and re-read the race descriptions multiple times because she loved them so much. One guy who knows most of the runners in the book thinks it might be the best running book he’s ever read. (Hyperbole, perhaps; but who am I to argue??) The fact that people who lived it think I got the story right (or at least mostly right) means so much to me.

And, in a different way, I am thrilled by the response I’ve gotten from non-runners. Folks who generally don’t read about running, or don’t even read a lot of non-fiction, have really enjoyed it. Obviously, that’s gratifying to my writerly vanity, but on a deeper level, their response to the book is important because I think 1984 was the greatest marathon in Olympic history and one of the greatest sports moments in history. I hope the book reaches people outside the running tribe, and introduces them to the greatness and power of our sport.

This answer sounds terribly braggadocious. So I’ll add that I’m sure plenty of folks read the first 20 pages and put the book down for good–or threw it across the room in disgust. But they’ve been kind enough not to tell me so.