Going Long: An Interview with Christine Yu

|

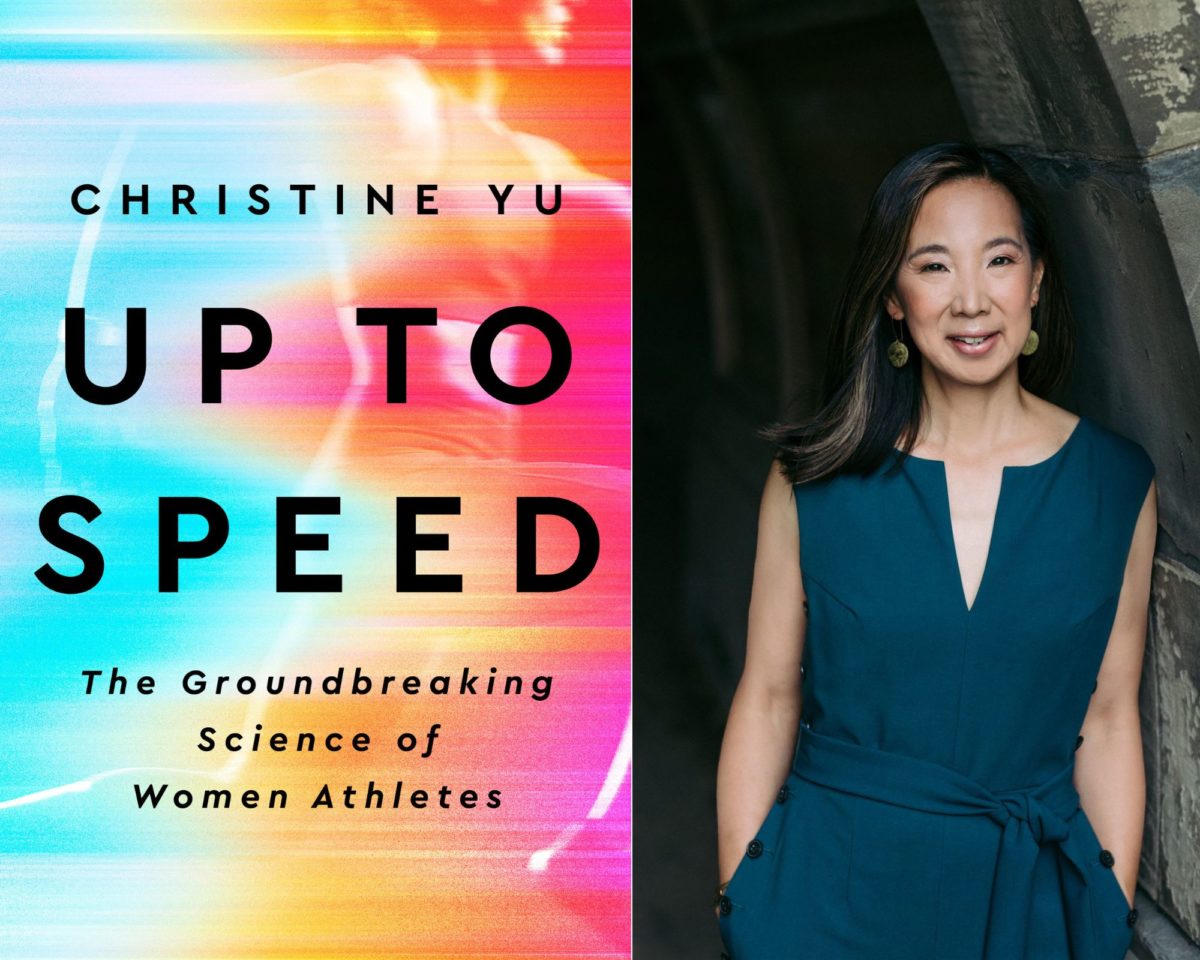

I recently sat down with Christine Yu, an award-winning journalist and author of Up to Speed, a new book that I would describe as a comprehensive guidebook that dispels false narratives around women in sport, dissects the latest research into women’s sports science and performance, and advocates for more and better research to improve the future experiences of active and athletic women across the age and identity spectrum. As a male coach of several female athletes I found this book to be an essential guide for understanding and navigating issues I’ll never experience, experiences I’ll never have, and differences that aren’t always obvious. It also opened my eyes to just how badly sports science research has failed women historically and also how systemic injustices have marginalized and excluded girls and women at all levels of sport. In this conversation, Christine and I talked about what the response to the book has been like since it was published in May, what surprised her most while she was reporting on it, how to accelerate sports science research for women, where systemic change needs to start, the challenges of writing about sex and gender, and a lot more.

Mario Fraioli: I have some questions that I’ve written down and others I’m sure will come up in the course of the conversation, but before I even start asking you questions, I just wanted to say thank you for writing this book. I don’t know who your target audience was exactly, but as someone who coaches a lot of female runners, it was kind of the comprehensive guidebook that I’d long been looking for, and I just wanted you to know that I appreciate that you put it out into the world.

Christine Yu: Oh, thank you. I appreciate hearing that. Yeah, I was often asked, “Who is the target audience?” I’m like, “Everyone? I don’t know.” I know for me, when I was thinking about writing the book and who I really wanted to read it, it was kind of younger girls and young women as well as the parents and coaches. I just wanted this information to get out there, and especially for those younger ages too, just to hopefully set up this foundation that can then lead to a good, healthy, long, athletic life.

We’re having this conversation in September. The book came out in May, so based on what you just said, I’m curious: Who has been reading it these past few months? Or, who have you heard from, and have any of those responses surprised you at all?

It’s been really interesting to hear the response, and it’s been overall really positive. You know, whenever you put something out in the world, you’re like, “I don’t know how it’s going to be received,” and it’s really kind of terrifying, especially after investing three years of my life into this. But the response has been really great. It has been a lot of active and performance-minded women, folks who are competing at the age-group level, some elite, some pros, who are just in the thick of this, and want to just know more about what’s going on, what they should be doing, what they can be doing, that’s one piece of it.

The other piece has been a lot of coaches, frankly, like yourself. Coaches who are looking for more guidance, who know that there probably is more that they should know or try to figure out, but there hasn’t really been any good resources that kind of brought stuff together under one roof. So that’s been, as I said in the beginning, that’s who I wanted to be reading this. And then it’s funny, because I also feel like the people that I’ve also heard from are a lot of older women. So I’m in my late 40s, but then also hearing from people in my age group, but then also older women who are like, “Yeah, what the heck is going on? What do I need to be doing?” And it’s frustrating, having lived through all of this already and then being in this next phase of life trying to figure out what to do now.

A couple of responses to that: To the last point about older women, my wife is approaching her mid-40s and things that I will never experience, she’s going through right now. My wife is a scientist by trade. She is scouring whatever she can to find as much information as she can about things like menopause, how should women change their training as they get into their fifth decade of life, what’s happening under the hood, all of that sort of stuff. And watching her go through that process, it’s eye-opening to me just how challenging and difficult it is—it’s also crazy to me that it’s 2023 and it’s not easy to find good information, or to know who to trust or how to apply it to your own situation.

Absolutely. So my husband’s a little bit older than me, and he would always joke, “Just you wait. Just you wait until you get into your 40s, everything goes downhill.” Or, “Just you wait until you get into your late 40s, everything’s going to go downhill.” And it would piss me off, frankly, because I’d be like, “That’s stupid. That’s dumb. That doesn’t make sense. There are things we can do.”

But then also getting to this age and recognizing that, yeah, things change, but trying to counteract the sense that there’s something I’m not doing. Why isn’t this working again? But I think what I’ve gotten out of talking to a lot of folks and researching and reporting this book is really realizing like, “Oh, wait, no. Yes, it is time and it is age. And there are literal physiological changes that are happening to my body. So it makes sense that things don’t feel the same, that things are working differently or what have you,” and we need to find a different way to approach this. It’s not going to look the same as it did in my 20s or my 30s, and it’s really frustrating, like you said, because there isn’t that much information to help guide you, and it’s very hit or miss.

Yeah, and it seems to me there are a lot of women who are aware that things are changing, but don’t know exactly where to look to understand what’s happening, and how that’s going to affect certainly their athletic pursuits, but just how they get through their lives as they get older, versus when they were 10 years younger, 15 years younger, et cetera.

Absolutely. I just had lunch with a good friend of mine who’s a little bit older than me, and she just feels really stuck. She’s in this phase where she’s like, “I’ve tried everything. I’ve tried all the stuff that Stacy Sims says or whatever, and it just tops out, it hasn’t been helping, and there’s no recourse.” And she’s also like, “I’m not ready to give up running. That’s not something that I’m willing to accept. I still have these goals. I still have these things that I want to do.” So what do you do with that? Even for myself, as someone who has been researching this and feeling like I’m in this phase, it’s partially because I’m injured, but I’m also in this phase where I’m like, “I get it. I get where this slide goes where you just start doing less and less and less. It makes sense why that happens.”

In the book you write, “Women have been neglected and misrepresented in the fields of sports science.” You’re a journalist by trade, you’ve done a lot of reporting on women athletes not just in your work, but as an athlete yourself. Talk to me about just how the pieces started to come together for you to eventually become what is now this book.

Through the course of having these conversations with athletes as I was interviewing them for stories I was writing, or I was interviewing experts for the articles I was working on, and it was almost in kind of passing or a side comment that they’d be like, “Oh yeah, but we actually don’t know that much about what goes on in women, or how this applies to women.” And I was like, “What do you mean by that?” It was just kind of surprising to me to hear that, and I didn’t really understand the full implication of what that meant. So it led me down this rabbit hole. Like all journalists, you get obsessed with something, you’re trying to figure out why. It led me down this hole where I wanted to understand, A, is it true that women are underrepresented in the sports science field or research, and then B, why is that? What has led to this that we don’t know as much about female physiology? But then more importantly was, what are the implications of that?

If we aren’t studying men and women to the same degree, or we don’t know whether or not these findings apply in the same way to women as they do to men, what does that mean for long-term health, for performance, for injury, all of these different things that we all care about? So that kind of was where this started. But then it was also this recognition that as a journalist too, being really frustrated by constantly reporting on the same things, or it felt like reporting on the same things over and over again, like body image issues, or eating disorders, or female athlete triad, or how women have more ACL tears than men. And there would be this article and people would be like, “Oh yeah, this is a big deal. We need to pay attention to this.” And then it would fade.

Then a year or so later there would be another crop of articles that would be talking about the same thing, and [I was] just feeling really frustrated that we weren’t actually getting anywhere with any of this. Why weren’t we understanding this better? Why are we still talking about this in the same way? So I wanted to move that conversation forward, but then also to bring those topics together under one umbrella, because I felt like there had to be a through line here. There had to be something that was connecting these different pieces.

Why do you think that cycle has been perpetuating for as long as it has?

I think overall it’s just that we don’t care about women’s sports or women’s issues as much as we do men’s. And I think particularly when you’re talking about sports, we don’t care about it to the same extent as men, or give it as much attention, or even if you look at just allocation of resources. We saw a couple of years ago with the NCAA basketball tournament and the differences in the facilities and resources provided to the athletes. It was a good example of where this discrepancy happens that we don’t even think about it. But then I also think about body image issues or eating—it’s framed in a way that it’s a feminine issue, and it almost feels like it’s a vanity thing in a way, or at least this is my take on it. It feels like it’s, “Oh, you’re just concerned about how you look.” It’s not a serious health or performance-related thing, whereas we know that eating disorders have the second-highest mortality rate of all mental health illnesses. And we don’t take that seriously enough, because we think it’s just a vanity issue, or because menstrual cycles, we only talk about it in relation to reproduction and fertility, and god forbid we talk about those topics, so we don’t pay attention to it. We don’t see it within this larger realm of how it relates to women’s health as a whole, women’s bodies and lived experience as a whole.

I’m glad you mentioned that because I think especially in the area of just eating disorders and body dysmorphia, speaking from my own experience as a male who has worked through these issues in the past, when I was trying to find help for myself it was almost always framed as a female issue—this isn’t something that males deal with. It was interesting to me just the way that it was portrayed in popular media at the time so I’m just glad that you bring this up, because I think all athletes deal with some version of the stuff, but then there are things that are really specific to females or to males, and it’s important that those two things get differentiated in that way, and given the attention that they deserve, really.

Yeah, absolutely. It’s really frustrating when it’s so dismissed, especially something like eating disorders or body dysmorphia. It’s so dismissive and we think that there’s so much blame put on the person themselves, versus the system in which we’re operating in, and then these unrealistic ideals that we’re functioning within. It makes me very angry.

In your years of reporting on the book, what were some of the biggest things that surprised you as you were just gathering information, talking to people, et cetera?

One of the biggest areas for me was injury. And again, it might just be my own personal experience with a lot of injury that kind of highlighted a lot of things. We do often hear about things like women have a higher rate of ACL tears, or with concussion, that women experience worse outcomes than men, and it’s almost taken as fact that it’s because there’s something different between men and women’s bodies that make women’s bodies more vulnerable or prone to these types of injuries. So it almost makes it seem like there’s something wrong with women’s bodies but some of the research that’s been coming out recently has really looked at taking a step back from just the anatomy, the physiology, the biology that’s going on, and really looking at the bigger picture of it, and realizing that some of these, what we thought were sex-based differences, might not actually be sex-based differences. It might just be a function of the environment in which those athletes are in.

So say something like concussion, researchers have found that if boys and girls actually receive specialty care or seek specialty care within the same timeframe—and I think it’s usually within a week, seven days—those disparities in concussion outcomes disappear. So if there actually were real sex-based differences in that, it wouldn’t matter when that person sought care necessarily. It begs the question then, why is that? It suggests that boys are getting to care sooner than girls, or girls might not be getting to care as quickly, so why is that? Is it because we don’t recognize the symptoms in the same way between boys and girls? Is it a question of resources? There are more trainers or athletic staff on the sidelines of football games than there are on the sidelines of girls soccer games, so it’s looking at some of those resource allocations too, and how that might play a role in some of this.

One thing you mentioned is how this isn’t an issue just in the sports science research, but also societally. As a male coach of female athletes, I’ve noticed there’s just a complete dearth of research when it comes to studying what’s going on with women, whether it’s how they respond to different types of exercise stress, what happens as they age, et cetera. But really, it’s just an extension of a bigger problem of a system that has long been just unjust and unequal on nearly every level. You talk a lot about this in the book, and to be fair, progress, however slowly it’s coming along, has been made to help level the field to some degree. But my question is: How do we accelerate it, whether it’s in the area of sports science research, which we know historically moves slowly, or providing equal opportunities for all athletes, no matter how they identify, when it comes to competition or even compensation or in some other area?

I think that it is a lot about the resource allocation. Taking something like sports research, like I said, it’s not only slow, but it’s expensive. It takes a lot of money to actually do these studies. So it’s making sure that people are actually going to fund this because some of the researchers that I’ve spoken to say they’ve often come up against a wall—they’ll propose a study, and whether it’s their head of the department or head of the funding agency will say, “Why do we need to do that? We’ve studied that in men already.” So it’s making sure that there’s adequate resources going to those types of scientific studies and all of that.

I think on a bigger picture level too, it is making sure that girls are getting the support they need at all stages of athletic development, starting from the grassroots level, starting from the youth level, and making sure that they’re getting coached well. I have kids, and a lot of their friends are playing travel and club soccer and all these whatever, crazy elite academies. For the boys, it’s very structured. They have a lot of resources going into that, and it’s not always the same for girls. But what happens in those young ages really matters in terms of how they develop their athletic skills or biomechanics, all of those things that they carry throughout their athletic life, so it’s making sure that the resources are there all the way up to the professional levels: the recovery, the pay, so that they’re not working multiple jobs to just do what they want to do. Making sure that, yes, it is the science piece of it to understand how they are responding to these higher levels of stress, and how they need to recover from those higher levels of stress. I think it’s just across the board we need to build a more solid infrastructure to support these athletes.

Riffing off that, do you think it needs to happen from the bottom up? Or the top down? Do we need to start creating these opportunities and equal resources at the youth level, maybe where your kids are at, and carry that all the way on through to the pros? Obviously, not everyone’s going to compete in high school or college or professionally, but you know what I mean, because we’ve seen it all the way up the chain. Or do we need to start from the top down? Start creating those sorts of things for the best of the best, and make sure the WNBA is getting just as much attention and resources as the NBA, or like we talked about earlier, at the NCAA level, at the NCAA tournament, making sure that men and women have access to equal facilities and food and all of these things, and hope that that kind of comes down. Just thinking about that out loud, what are your observations there?

That’s a really great question. I’m like, “I want it both ways,” but I think the pragmatic side of me will say that I think we focus on the top level of sport, because when we have that interest and that enthusiasm, and we build the case for women’s sports, that it is this thing that we care about that’s worthy of investment, those federations, those leagues will have to make sure that they’re investing in taking care of their athletes, because there is no league, there is no sport without those athletes.

When you build that case at the top level, then it is a bit of that trickle-down effect. Then it does justify, OK, why are we investing in the NCAA level? Why are we investing in the high school level and the youth level? Because you do need that pipeline of athletes to get up to whatever professional level we’re talking about here. But I think that at least in our society, it does start with the top because that’s where the glitz and the glamor and the attention is, for better or for worse.

Yeah, I agree with you. I think that’s right for all the reasons that you just stated. And if I’m putting my coaching hat on, I coach mostly age-group athletes, and I do coach some elites too, but whether it’s training theory, whether it’s products that companies are putting out, usually they start building them for the top levels first, and then we take learnings from that, and we kind of apply it all the way down. It becomes sort of standard practice and I think the same sort of thing can happen just when it comes to opportunity, research, et cetera, just in sports for all people.

Absolutely. That’s where the sponsors are and that’s where the folks are going to want to put their money in, right?

Exactly. Toward the end of the book, one of the things that you wrote was about the oft-cited statistic that it takes an average of 17 years for research findings to be incorporated into clinical practice. And you kind of give the example that, if a new study is released on women the same day that a girl is born, she’ll likely graduate from high school before any of that really gets implemented. We know science takes time, and it’s to everyone’s benefit that that process is not rushed. But how does science speed this up without taking shortcuts? Do you think there’s a path forward there?

I do. It’s so frustrating. When I came across that statistic, and really thought about it, I was like, “This is ridiculous.” That is like a life… childhood, so many years, but like you said, the reason that it takes so long to trickle down into clinical practice is because there are a lot of studies, and science moves very incrementally so you’ve got to make sure this happens, and then double check, and confirm it, and then slowly step forward until you can get to these consensus based guidelines.

And I think that that’s where a lot of the frustration lies right now, especially on the women’s side because like we’ve talked about, women are really frustrated and really want answers and want to know what to do now, and don’t want to have to wait 17 years until there is some consensus based guideline on something like this. I think what science can do is, obviously, they have to do these studies that they’re doing, and do these controlled studies and whatever else, but I think that they could also start to kind of look at more case studies too—not necessarily one-off as in outliers, but just using case studies of different types of athletes, probably starting with elite level, professional athletes, where the interest is going to be, but using those two as a way to start to highlight some of the things that might be going on, and that might spark some additional research questions, or that might provide some sort of guidance or at least ideas for people to start playing with.

Because frankly, at least from my perspective, for a lot of women, a lot of this is going to be what scientists call, me-search. I feel like that happens anyways with any sort of fitness thing, you have a plan and you have to see what works for you. Or you might give me some training plan based on whatever, but my body might respond differently, especially if this is the first time we’re working together, so there’s a lot of adjustment that has to happen. I think doing some more case studies, doing some more qualitative work, trying to understand some of the stuff that’s happening there. And scientists can actually do a better job with the communication portion of it because right now all of it is behind paywalls, it’s in these academic journals that nobody wants to read. It puts you to sleep. So how can these research institutions and scientists also do a better job communicating to the general public?

I agree. I had that thought as I was reading your book. I’m like, “Part of this,” and it’s not the only problem, “is a marketing issue.” It really is a marketing issue because more research needs to be done, but there’s a lot there that people just don’t have access to, don’t know how to interpret, it could very well be helpful, and it’s just kind of sitting there, and no one’s doing anything with it. I feel like just taking that which exists and making it more accessible would make a big difference.

I think that there’s always this kind of friction between the scientific community and how you communicate that out in a way that is accessible. But yeah, I wish they would do that better.

I’ve got a few more questions for you. The first is: How challenging was it for you to write about sex and gender given that there’s a wide range of ways in which a person identifies these days?

To be totally honest, I didn’t want to write about it at all. When I was first talking to my editor about the book and had put together my proposal and all of this stuff, I didn’t want to touch it. I think I was scared of how to approach it, or wanting to make sure that I approached it in a way that wasn’t exclusionary, that didn’t fall into this trap of bioessentialism, and all of these terrible arguments that we’re hearing now in terms of all this anti-trans legislation in sports. I was terrified of it. I was also terrified that people would come after me, or use the book in some way to bolster their argument in a way that I didn’t intend. So I was like, “I don’t want to touch it. I don’t want to talk about it.” And she’s like, “You can’t not talk about it.” I’m like, “Fine.”

It was really hard because you are talking about both science and sports, which are two fields that are essentially predicated on the binary, on this male-female split, and in ways that are really separate. So it was really hard to try to find that middle ground to talk about it and to acknowledge the lived experience of people from across the sex and gender binary spectrum in a way, again, that felt authentic, but that didn’t also feel like I was calling out or criticizing or anything like that. It was really hard. I had a couple of people read some of that. I have a little piece too in the introduction and talk about how I use language and the way that I use language. I felt like that was important too, to set the tone for how I was talking about using phrases like female versus male, and women versus man, and that type of thing.

Have you received any pushback at all in that regard?

I’m not supposed to read reviews but there’s been just a couple of reviews that have come out, and people calling attention to that, and being like, “That undermines the whole argument when she says things like, ‘People with uteruses,'” or something like that. So there’s things like that, but overall, knock on wood, it’s been pretty quiet on that front.

Going back to what I said at the beginning, for me, I really view your book as a guidebook. If you want to know more about female physiology specifically, this gives you the tools to be able to explore that. Or injury rates amongst women versus men, why that may be the case, it can help point you in that direction. And so on. I don’t know if you’ve had time to think about this, but what do you hope the lasting impact of this book and your work is?

It’s really funny when you put something like this out in the world, and especially I feel like a book in particular, there’s so much hoopla around publication day, trying to make bestseller list, and all this other crazy stuff that you kind of lose sight of what your actual hope and goal for this work is. I know for myself, I was definitely getting kind of caught up in a lot of that. But for me, I really hope that this does have a long life, that this has a really long tail, that people continue to keep discovering it along the way, recommending it to folks along the way. There wasn’t anything out there that really pulled all these different topics together under one roof and I felt like that was a big gap that I saw in the field and in the market that I wanted to be able to provide. I didn’t want to do something prescriptive because again, that’s not my place as a journalist to be providing that type of prescriptive advice, but also because this is ever-changing. This is kind of what we know now and understanding where we came from, so that we can continue to interrogate these systems and ask these questions in a way to help us continue to move forward. So yeah, the fact that you see it as this guidebook and kind of something that does have a longer tail is very encouraging to me, so I appreciate that.

Not to stress you out at all, but do you think this is something that you may need to update a few years from now, and have it be an updated version of Up to Speed as more and more research comes out? Or is that just something you’d prefer not to think about because it’s too fresh at this point?

I’m trying not to think about that. We put the manuscript to bed May of 2022, so it was a full year before it actually hit bookshelves. Even in that time, and even before that, when I had to really stop writing new material and just focus on editing, there was this time when I stopped looking at new research, maybe January 2022 or something like that, because at some point you just have to stop. Even in that amount of time, there’s been a lot of change in the research landscape, and a lot of more interesting studies that have been coming out, so yeah, unfortunately, maybe I have to update this, and add some addendums and stuff.

Yeah, I know for any author you’re glad to get the book across the finish line. Then you’re like, “I don’t know if I want to go to that finish line again anytime soon.” I get that.

Definitely.

Christine, thank you for your time, this conversation, and your book. I hope more male coaches in particular pick it up because this is just a lot of stuff that we will never experience or have to navigate on our own. But if we’re going to work with females, it’s important that we have an understanding of certain things and also an understanding of where to go to learn more. Your book definitely provided that in a more comprehensive way than anything else that I’ve seen out there, so thank you very much.

I really appreciate hearing that coming from you. Thank you.