Going Long: An Interview with Sarah Gearhart

|

I recently had a conversation with Sarah Gearhart, author of We Share The Sun, which comes out on April 4 wherever books are sold. I received my copy a few weeks ago and devoured it in two days. It’s part biography of Patrick Sang, the legendary coach of Eliud Kipchoge and other distance-running superstars, and part behind-the-scenes peek of the inner workings of his training group based in Kaptagat, Kenya. I was fascinated to learn more about the architect responsible for multiple world records, major marathon wins and course records, numerous global medals, and other incredible competitive accomplishments. Coach Sang is a private individual but he opened up to Gearhart in a big way and she did a wonderful job painting a portrait of a man who is revered not only for the successes his athletes have experienced in sport, but also for his holistic coaching philosophy and the impact he has on the rest of their lives. In addition to telling Sang’s story, Gearhart shines a light on many of his athletes, most of whom aren’t well known beyond the races they’ve won or the times they’ve posted.

Mario Fraioli: The book, which I loved, is part biography, but also part peek behind the curtain of the greatest training group in the entire world. Eliud Kipchoge, at this point of his career, he’s an internationally renowned star in the world of running. And because of the sub-2 projects, and his world records, and all of that I think he’s recognized outside of running circles. But Patrick Sang is the man behind a lot of his success and really has been there for him every step of the way. Not a lot is known about him or the inner workings of their training group, aside from knowing they live a simple, monastic lifestyle while they’re at camp. So I’m just curious, where did the idea for the book come to be?

Sarah Gearhart: Yeah, so that’s an interesting story. What happened was in Spring 2021 a literary agent in New York reached out to me about a story that I wrote for Runner’s World magazine the year prior. And he was like, “I’m curious if you’re interested in turning this into a book.” And the story was about Gordy Ainsleigh and the first 100-mile ultra through the Sierra Nevada. And I wasn’t really interested in exploring the idea of turning that into a book and expanding on that. Just at the time, it wasn’t the direction that I wanted to go. Not to say that it’s not deserving of a book in the future, and I’m not totally closed to it in the future, but it just wasn’t the direction that I wanted to go. And for the longest time, I had always been really interested in stories about East African runners, because I just always felt that in Western media, the human side of them wasn’t really revealed. And I’m sure you can agree with that, that when they’re written about, it’s often in terms of numbers: what number they can produce, what place they get. I had profiled Emmanuel Mutai at the 2017 Boston Marathon. He was the number one entrant in the field. And at the time, I think he was the fourth-fastest marathoner [of all-time]. And I interviewed him and I was thinking, “I really want to go to Kenya.” Because even just having a little bit of conversation with him, I just thought, “there’s so much there.” There are a lot of rich stories over there that I feel like need to be brought to life and can be brought to life.

Anyway, so what happened was when the agent reached out to me about that story, I said, “Well, that’s not what I’m interested in, but here is what I am interested in.” It was more so wanting to have a book of profiles about some of these runners. And he thought initially that that’s not really going to sell—that sounds more like an anthology. “So why don’t you keep thinking about this idea?” And then it crossed my mind; well, why not talk about the man who is behind producing some of these athletes? And I was researching, and when I came across Patrick Sang’s name, the information affiliated with him, it’s just so incredibly limited, like you said—he went to school in the U.S. and that he competed in a couple of Olympics. Everyone knows his name attached to Eliud Kipchoge, et cetera. But beyond that, there wasn’t that much there. And so I was really curious to see if maybe that could become something more.

And so as it happens, we have a mutual contact, so I reached out to that contact, who is a sports agent, and he has known Patrick for, I want to say, 20 something years. A really long time. We had a long conversation. He was like, “Well, I have to be honest. I can’t say that he’ll be open to this, but I’ll at least talk to him.” He made the preface that Coach Sang is really private, which is true. And that’s why you don’t see that much about him in the media, because he is extremely private. And so what happened was the agent talked to Coach Sang and Coach Sang was at least interested in hearing the idea. And so I presented an outline of the chapters that I had in mind, and he thought about it. That was Spring 2020 and I was incredibly persistent. I joke that I feel like looking back now, I must have texted him on WhatsApp every week, because I really wanted to do it. I was very persistent and it wasn’t until September he actually agreed to do it. And he told me, “I normally wouldn’t want to be a part of something like this, but I’ve considered it, given it a lot of thought. I consider this an opportunity or a gift that I don’t know what to do with.” And so yeah, he said yes, and that meant a lot to me. So we had a lot of conversations leading up to me going to Kenya and actually having a one-on-one in person. But I remember some of those conversations, we would talk about everything but running. We would talk about politics, world affairs, education, meaningful things, and then running would always be at the tail end. And I just knew pretty early that he’s going to be a really great conversationalist. He’s just so thoughtful and he’s so intelligent. I remember when we sat down, this was April, 2021 when I went to Kenya for the first time and we sat down for our first in-person interview—it was four hours, so that was a little painful to transcribe, but I remember we talked about so many things and he was like, “You’re persistent.” And he later told me that he was testing me the whole time. I think he just wanted to see or understand how serious I was. And I was definitely really serious, because intuitively I knew that he had an incredible story.

Well, and he’s a coach, so that’s just a quality that he’s going to admire in another person, because many of the athletes that he works with are the same way. To be good at anything, you have to be just persistent, even when you keep running into walls or getting denied. It sounds like he probably appreciated that. And then just hearing you describe how it wasn’t an immediate yes—he just really thought it through. From afar, knowing what I know about Coach Sang, that strikes me as unsurprising, really, that he was just really thoughtful and considered and then had a very definitive answer. It was either going to be, “Yes, I’m all-in on this,” or, “No, I’m not going to do it at all.”

The interesting thing is that I was super close to giving up, because we just went back and forth so much and I just kind of felt like he’s going to say no, he’s going to say no. And this was in the middle of the pandemic and everyone was worried and concerned and we didn’t know about the Olympics, et cetera. And so he put off the decision for a while. And so I was really close to actually giving up, but I was like, “No, no, no, no. I have to try. I have to keep trying.”

So that initial trip that you took to Kenya, how long were you there?

I was there for seven weeks. So initially I had planned on being there for three weeks, but I extended my trip because I also needed to finish writing my proposal. And I just feel like it would’ve been really difficult to write it if I wasn’t in that environment, because I can’t write what I can’t see and what I can’t hear and things like that. Plus, where I was, I was in the Rift Valley and I was in the countryside, so I was around farmers and runners, and there’s nothing else to really do besides run and sleep and work. So for me, I also wanted to be there because I knew it wasn’t going to be distracting.

You just mentioned how you were still finishing the proposal while you were there. Was it a tough sell to the publisher at that point, or was it kind of a done deal?

I was pretty confident that someone would take it. What happened was I actually finished the proposal and it was fully edited while I was still in Kenya. And then my agent, he had sent it to multiple publishers in New York and three of them wanted a meeting. When I got back to New York, it was the day after I got back, and it was jet lag, and I had to do three meetings all in the same day, I think. Then we had an auction and it was like that. I say it like it’s easy, but it’s really not easy to sell a book.

MF: Had you spent any time in Kenya before taking this trip there?

No. No. But I had always wanted to go.

What were your initial impressions when you arrived in the Rift Valley and showed up at training camp?

It’s quiet. There’s a lot of dirt, iron-colored dirt, and it gets all over your shoes. Everyone is really humble. Really, really humble. Where I was, the view, I was really close to the escarpment and that was really amazing to see. I found it really inspiring. It was a slower pace of life from what I’m used to, and I think what I appreciated the most was just how welcoming and kind people are, and communal. I think that’s really typical of certain parts of Africa. I’m in South Africa right now, and that’s really typical of the lifestyle. I just really appreciated it, because being in the U.S., people are really individualistic, and you just get a totally different vibe here and I really appreciated that.

One thing that really, really surprised me was that recreational running is not a thing at all there. I’m someone who runs, and I’ve been running for a really long time. My average run is 10 miles but I do it slow. There, no one goes out and runs for fun—it’s because they want to make it a career. I remember one day I was running and a woman came up to me and joined me and she was jogging and she was like, “You guys in the U.S., you just run for pleasure, and we run for a job.” And yeah, that’s very true. I have never been in an environment where it was that serious—they’re so extremely serious. No one listens to music, they don’t talk. That’s another thing, too. No one talks. It’s not like you’re running and you’re catching up about life. It’s so silent and businesslike and I really appreciated that. The perspective is so different. It was unique to see. And also the fact that with someone who’s running 10 miles most days of the week, they’re considered lazy in a way. I run once a day, everyone’s running twice a day, and it’s like, “You’re running 10 miles. Good for you. Are you going to do more on top of that?” That’s how I felt. That’s kind of crazy.

You had mentioned before we started recording how it’s really not typical for journalists to spend time at training camp. It’s very limited access, usually just once a year. How did you feel, having been there for seven weeks, and just being around the entire team and the staff on a regular basis? Were they welcoming or was there aver any tension there?

I felt welcome the first day that I arrived. In fact, after the training sessions, I was welcome to go inside the camp and sit with the coaches and have tea and breakfast. It was like that. And actually, this recent trip, when I presented the book, they had said to me, “You’re part of the family now,” which was really nice to hear. I didn’t feel any tension at all. I like to be like a fly on the wall and just be there to observe and listen and not be distracting, as much as I can be. They’re very welcoming and they’re very communal.

Next time you’re training for a marathon, you’ll just have to go back and do a training camp there. What an opportunity that would be.

Oh my God. It is actually really, really hard to run there though, so I don’t know if I’d want to train there myself, because it’s really hard.

What made it really hard? Was it the altitude? Was it the dirt? Was it just figuring out where to go? Or some combination of all those things?

Not figuring out where to go. The fact that you’re 8,000 feet altitude, so there’s that. And everything is hills, so you’re not only at high altitude, but you’re also running uphill. It’s really, really hard. I ran mostly by myself because I definitely cannot keep up with any Kenyan, not even a local. The one time I tried, it was a Wednesday, and there was a group of seven men and women, and they were just doing an easy run. And I was like, “That looks feasible.” So I sped up and joined them. I didn’t say a word, and they just glanced at me and didn’t say anything. We were running, and then I felt my arms get numb, because we were actually running faster than what I was normally used to. I make it I think a mile, a mile and a half, and I stop. I was like, “I can’t.” So just for a little bit of scale, they are very fast. Even their easy runs are fast.

So when you embedded yourself in the training camp and you’re just being a fly on the wall, you’re obviously paying close attention to everything, but particularly Coach Sang and how he goes about his day and how he’s interacting with the athletes. At this point you probably had a decent understanding of how he was, but what were some of those initial observations when you first arrived and actually saw him do his thing?

It’s funny, you can hear him laughing from across the field. There are occasions when he is really serious and there are occasions when he’s chuckling all the time and he cracks a lot of jokes. I think I was kind of surprised to see that, because I was expecting all serious, all the time. But he’s not always like that. It really depends on the workout. How calm he is when he talks to athletes. I think I used the word “athlete whisperer.” He’s just really calm in the way that he talks to athletes. I’ve definitely been around enough coaches where they scream and they curse, and he’s not like that at all, so that was really nice to see. And everyone’s responsive. They don’t talk back to him. They’re really respectful and they do what he says.

There’s a pretty big group of athletes at camp, and Eliud Kipchoge is the most recognizable one. But you’ve also got Geoffrey Kamworor, you’ve got Faith Kipyegon—huge, huge names in the sport. As a coach myself, your relationship with every athlete is going to be a bit different. How is Coach Sang with some of those more recognizable athletes versus maybe some of the younger folks who were in camp? Did he treat everyone kind of the same?

One hundred percent. That was really nice to see. There’s another camp across the street and they all kind of train together—even the junior athletes, he treats them all the same, and it’s so nice to see. Everyone is equal. What I thought was really lovely too is that everyone has a nickname, and yeah, he’s just really funny in using their nicknames. It was nice to see so many good successful athletes altogether without egos, because that doesn’t ever happen. And this is mentioned in the book, but there aren’t really workers at the camp—[the athletes] all take turns doing certain things. They’ll do a hard run and they’ll maintain the camp, which is also unique to see. Everyone has a responsibility.

What surprised you most when you were reporting on the book? You had mentioned how people in Kenya don’t run for fun or recreation or just general fitness, so I suppose that would be one thing. But you’ve spent a good chunk of time there. As you went through the weeks, were there any things that you were like, “Huh, I didn’t expect to see that,” or for X, Y, and Z to happen?

I watched about three races while I was there, and that surprised me a lot, because I had never been at a race where I saw the competitors barefoot or in dresses, but that’s what they had to work with. It’s really interesting watching a competitive race in Kenya, because as Coach Sang said, in the U.S., for instance, you’ll have a small percentage of elite and local elites, but in Kenya everyone is elite. The intensity, it’s on another level, so that was really unique to see.

Also, during the reporting, what surprised me was some of the background information about Coach Sang, which I put in the second and third chapters, which are really personal and really sensitive. I was really open with him about all of the material. After I finished writing the first draft, he read the whole thing, and he also read the full second draft as well. He had told me that he had shared the first draft with his sons, and one of his sons said he was surprised by some of the information. He was like, “Who are you?”

Wow.

I wasn’t expecting that. He told me that when I was at the Berlin Marathon last year, and he laughs about it. I was surprised. When I was at the camp [recently] and I gave Eliud a book, I said, “I wonder what you’re going to learn about your coach in here,” including the meaning of his name. He is a really private person, and I only wish that I could have included more, but I also wanted to be mindful and respectful of his privacy as well.

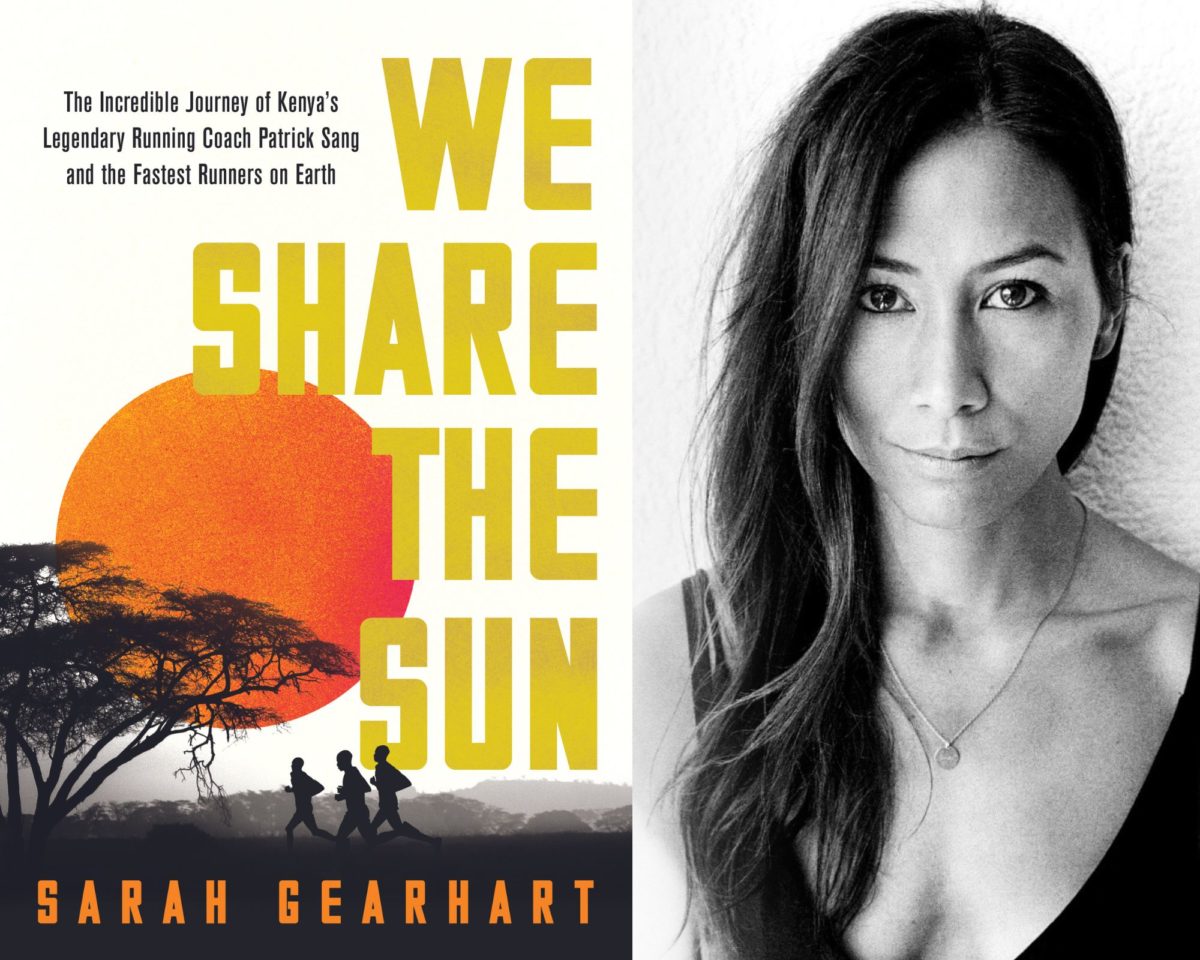

Two more questions before we wrap up. The first is just the name of the book: We Share The Sun. The cover image is beautiful. It’s a silhouette of just three runners running toward this big orange sun. I’d love for you to just share how that came to be.

It’s funny because I actually had a totally different title in mine, which was really more generic, kind of vanilla, and I’m so glad that I changed it. The title is actually an English translation of a phrase that I learned in Swahili, which means “we share the sun.” The meaning is not meant to be surface level in any way. The fact that they do run and they share the sun, it’s not meant like that in any way. Really I think about it in terms of this concept of ubuntu, that’s the best way that I can explain it. I want people to really think about the title and for me not to explain it so much. But it’s that—it’s like we’re all equal and we’re all here together and I think it’s really important that you look out for your neighbor and contribute to society and your community in a positive way that is uplifting. You can want to succeed but also don’t forget about the person behind you and lift them up along the way. That’s one description of how I put it but I really like the concept of ubuntu in terms of the purpose of humanity. That’s it, really.

And just building off that: What were some of your biggest takeaways? You’re an experienced marathoner yourself. It’s a big part of your life. You were running a lot while you were there. Kaptagat couldn’t be any more different from New York City, which is your home base. What were some of the lessons and takeaways that you brought back with you and tried to implement into how you go about your day and how you approach the sport?

I hate to really admit this, but I don’t do speed training. My marathon PR is 3:26 without speed training and I know better, because I also ran when I was in high school and college, but I know I need to implement that. I really want to implement that more when I train for another marathon.

I think one of the biggest takeaways is actually the mental component, the mental endurance. OK, so here’s a story. In December 2021, there was a Thursday long run of 40K around Kaptagat, and it’s a very hilly course. I think they actually run [at] over 8000 feet. There is a runner who is an 800-meter specialist and I think he was trying to lose weight, so he actually did the whole route. He ran 2:51, which is the equivalent of I think a 3-hour marathon, and he’s an 800-meter runner. I was so impressed to see that and I even commented to Coach Sang, and he was like, “Yeah, it is in your head, the mental component.” I have thought about that and replayed that training session in my mind throughout my runs, especially last summer when I was marathon training. I think about it in terms of what is actually really hard, it’s in your head. If an 800-meter guy can go out and just run the equivalent of almost a marathon, and he can do it kind of casually, you have to think, whatever you have in front of you, it’s actually really manageable and you can do it. So I think about it in terms of that: What does it actually mean to push yourself? If that makes any sense.

It totally makes sense and I think it’s a great takeaway for anyone who’s reading this interview. And with that, I have one more question: You went into this with some curiosity because a lot of the East African runners, the Kenyans, certainly a lot of Ethiopians, they’re just fast men and women, and we don’t really know much about them aside from what their marathon PR is, or if they set a world record. And although this book is very focused on Coach Sang and the athletes in his group, what are some of the biggest misconceptions that the average Western running fan has about East African runners?

I think the language barrier, for one. Being there in Kenya, I can say that pretty much everyone that I interacted with, they speak three languages: It’s Swahili, English, and then whatever their mother tongue is from whatever tribe they’re from. But you can talk to them in English and you can understand them. I’ve even had questions of, “Did you need an interpreter?” No, I didn’t. So that, the language barrier. I also had people ask me, “What was the water situation like? What was the internet like?” Of course it’s not as developed as being in New York City but that’s not even a fair comparison. I was fine being there. I managed perfectly fine. I think something I learned that I think is important to share is that you really don’t need that much. I think my experience there has made me reconsider what is important in my life. You really don’t need that much.